Smart gender policy

Women’s rights, supporting women’s economic participation and female entrepreneurship are priorities on the Trade and Development agenda of the Dutch government. However, how can we effectively support this agenda in a complex sociocultural context in programmes with so many other priorities? In the East African context, focusing on family business and recognizing the specific contributions women can make within agricultural small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) and on family farms can be inclusive, sustainable and effective ways in supporting this agenda.

Gender is a term from development jargon that often unleashes a wide range of emotions. On the one hand, the term may conjure up images of the struggle for social justice for half of the worlds’ population. A term that resonates with the idea that patriarchal domination is a central part of what is wrong in the world today thanks to wars, poverty, social exclusion and environmental destruction. On the other hand, the word gender can give rise to sighs of irritation, lack of interest or lip-service to political correctness. Or even worse, reactionary misplaced notions that men are discriminated against, that the boy child is being neglected and that there is a need for initiatives for men’s empowerment like “Maendeleo ya wanaume”, Swahili for “men’s development”.1

As a father of two daughters, I am a stakeholder in women’s empowerment. As a public service professional with work experience in more or less gender balanced teams, I am a fervent supporter for more women in higher-level management positions. Yet at the same time, I am convinced we have to be smarter when it comes down to gender balancing. While men and women worldwide should have equal rights and equal opportunities, it should be recognized that men and women are not the same.2 A smart organization, be it an office, a company or a family unit, is able to build upon the often various talents and strengths that women and men have to contribute, and involve both in decision making and create an environment for both to excel. Let me illustrate this with an example of a SME family-run agribusiness I have come across in Kenya in the field of food security.

AML Ltd.3 is an exporter of fresh produce in central Kenya. The company grows about 20% of the produce it exports on its own farm and buys the rest from neighbouring smallholders. Recently, AML has moved its grading and sorting centre from the industrial area in Nairobi to the farm in order to reduce costs and build a stronger relationship with the local community and its suppliers. The farm was established by a family man in the 1970s when he was working for the government. As he came from a densely populated area of Kenya and a large family, he had a small chance in inheriting land. Yet he felt that a man must have land. So he made frequent trips in the weekends to look for agricultural land to buy. Finally, he found a decent piece of land in the former “white highlands”. As a “telephone farmer”,4 he grew some maize and pyrethrum and kept a herd of sheep as was common in the area.

Meanwhile, the mother of this family started growing garden vegetables at the AML farm over the weekend after her weekday nursing shifts in Nairobi. As a result, she started selling fresh produce to her colleagues at the hospital. Empowered by the business experience, she followed the example of a friend and started exporting fine beans and snow peas to Europe. She started to do well running her own trading business and soon decided to quit nursing and focus full time on AML. Several decades later, the next generation has joined the company. The son went on to university and became a banker. After five odd years of working as a banker, he decided to quit his job and join the family business as the marketing manager. Even the daughter who studied in the UK, worked in IT and started a family has since moved back to Kenya and joined AML as an office manager.

In this example and in other family companies, one can see that women and men are playing complementary roles,5 though one must look beyond the obvious. In public, at stakeholder workshops or when welcoming visitors, the husband will often take the spotlight. He will often formulate big ideas or far sighted plans. However without the diligent management of the mother, many of these family enterprises would have never survived, or even seen the light of day. Combining men’s and women’s talents within a family business – a truly balanced joint venture – seems ideal for a SME: balancing innovation and risk management, seizing opportunities and yet tending to the social and financial bottom line.

So what does this mean for agricultural development programmes that support family businesses? Too often in projects, gender is a box to tick as the donor is expecting this. In such cases efforts do not go much beyond formulating gender disaggregated performance indicators: improve the incomes of 4000 farmers by 10%, of which 50% women. Yet this is blind to the relations and realities behind these figures. Let me illustrate this reality behind the figures with another example.

Once I made a farm visit. A man was introduced to me as the farmer. Dressed in brand new overalls and followed by his silent wife, he led us around the farm. Speaking Swahili, at times he seemed hesitant when responding to my questions. Then I asked who actually did the work on the farm: him, his wife or was it a joint venture? It appeared that the husband was a tailor in a nearby village while the wife tended to the farm. His salary was used to invest and he was the owner of the land so he had the final say on investment decisions. After this question however, the wife felt more confident to comment on farm operations and plans for the future – in good secondary school English no less.

If a development organization would not take a smart gender approach to family farms, it might for example target the husband for training6 and not take into account that the wife is in fact managing the farm work. This would of course not be an effective way of providing advice to improve farming practices. If a development organization takes a simplistic gender approach, it may not select to work with the family farm described above in an effort to achieve their target of number of women farmers reached. Alternatively, the organization may decide to focus on supporting only women. This might likely lead to frustration, for example, if the wife might know what is right for the business but might not be able to convince her husband that change or a certain investment is needed.

Thus, a smart gender approach means understanding the dynamics beyond the obvious. It means recognizing and valuing the role that both the husband and the wife play and encouraging joint decision making. By stressing the potential of a joint venture husband and wife partnership, one values their mutual interdependence. One way of doing this is to identify role models of strong women active in business and recognize the talents that make these women successful in relation to their husbands. At the same time, it is worth recognizing supportive men that are providing encouragement and open space for their wives to succeed. In doing so, recognizing that being a strong man beside or even behind a strong woman enhances rather than diminishes masculinity.

In short, a successful gender strategy is based on the added value and complementarity of both women and men. Men have traditionally held women back and reinforced male domination. Only when we men free our minds and value the contributions women make, can we expect our families, businesses, organizations and societies to really thrive.

Read more about the topic “Gender” in the F&BKP Knowledge Portal.

Footnotes

- 1. Beyond these reactionary emotional statements also lie genuine, empirically justified concerns about a “crisis of masculinity” in Kenya.

- 2. Every individual is different. However, if I may be so bold to generalize, one could say that men tend to overestimate themselves, like to compete, think big and take risks. Women on the other hand tend to underestimate themselves, yet are better at collaborating, have an eye for the needs of others and make sure things get done. If I may be bolder yet, I would say that women make better managers, and men better leaders.

- 3. I have anonymized the company name to protect the family’s privacy.

- 4. An urban professional engaged in farming on the side.

- 5. In truly successful and sustainable family businesses the next generation is also involved. The husband and wife have a succession plan to ensure the business or the farm will continue to prosper rather than be stripped of its assets and be demolished when it is time for the children to inherit.

- 6. On for instance good agricultural practices or farming as a business.

Great post , its very informative and interesting post ,thank you for sharing this blog.

An interesting perception on the prowess of women in agricultural family enterprises. Reading through I can quite identify with quite a few of exporting companies with a similar disposition here in Kenya.

Women’s economic empowerment requires everyone’s support. As such I appreciate the opinion of Melle Leenstra and agree with him that the contribution of women to the agri-food sector is still largely unrecognized. It takes a gender-lens to make them visible. It is not for nothing that RootCapital refers to many women in agriculture as hidden influencers. In that respect it is high time that we abandon the term ‘farmer’ with its male connotation. Let’s consistently start talking about ‘male and female farmers’, as DCED suggests. However, sometimes glasses need to be cleaned a bit. What more can we see when we look at women in agriculture?

Leenstra makes a plea for paying more attention to family businesses, instead of focusing on ‘women only’. Indeed, it is key to engage men and look at gender-relations, instead of at women in isolation. We need more gender-aware programs that focus on men as well and aim to influence their attitude and behavior. E.g that reproductive tasks, such as looking after children or cooking, can also be done by men, as it enables women to attend technical training or join board meetings of their cooperative.

There are numerous stories that highlight the psychological and emotional challenges that women face while dealing with male ego’s in family or business relations. In the end women are expected by society never to comprise in being housekeepers and mothers. The lack of basic services and proper child care and stereotype role models in media always reminds them of this.

I like to comment to the, in my view rather stereotype, portrait of a -small holder- family enterprise. The ‘picture’ we get is of a complementary couple with the husband as ‘leader’ and the wife as ‘manager’. Even though all stereotypes hold some truth, this runs the danger that important facts are ignored. Indeed most SMEs, whether they have a male or a female owner at the top, are in fact family-run businesses. Yet, one third of the SMEs globally are officially run by women entrepreneurs. Let’s also not forget that up to 30% of farming worldwide consists of female headed households, either the facto or the jure (FAO). 30% is a substantial number.

Moreover, whether women are ‘single’ or in a joint setting with men, ‘being a woman’ still implies that the far majority of them lack access to essential resources and assets to optimize their contribution to agriculture and achieve their full human potential.

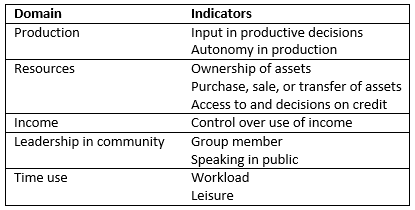

The Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) developed by IFPRI and partners offers a good overview what women need. The tool measures the roles and extent of women’s engagement in the agriculture sector in five domains (see table). It also measures women’s empowerment relative to men within their households.

It reminds me of a blog on the Top 10 of Things That Women Invented. The general idea of an inventor is of a male, Einstein. Indeed at the end of the 20th century, only 10 percent of all patents were awarded to female inventors. The blog tells about Sybilla Masters who came up with a new way to turn corn into cornmeal. However, laws at that time (the year 1715) stipulated that women couldn’t own property, which included intellectual property like a patent. So the patent was issued in the name of her husband.

In other words, we always need to look beyond the obvious and analyze which resources women have access to. So that complementarity becomes interdependence between equals and that women not only have both the mental, but also the material means to manage and be treated in their own right.