Nutritions for depleted African soils

To contribute to the objectives of the IYS 2015, the F&BKP commissioned ImpactReporters to publish seven background articles on themes related to international soil and land use and enhancing food security. The second article ‘ Nutritions for depleted African soils‘ has been written in Dutch by Hans van de Veen of ImpactReporters and was published on the Kennislink website on May 22, 2015. Please find below a translation of the article in English.

Nutritions for depleted African soils

Nowhere is soil fertility deteriorating as rapidly as in Africa, posing a direct threat to local food supplies. The looming catastrophe is attracting increasing attention but the way in which African farmers can best revitalise their land has become the subject of fierce debate. The Netherlands Fertile Grounds Initiative is arguing for a coordinated strategy to manage nutrient flows. ‘Transport compost and manure from the cities to rural areas.’

Brewing beer generates lots of organic waste, full of nutrients. ‘We’re currently in talks with the Heineken brewery in Ethiopia to see if that can be used for the benefit of local farmers,’ says Wageningen-based soil researcher Christy van Beek. The volumes of organic waste in Africa are still relatively small, nothing like those produced in the world’s more industrialized regions. But they are on the increase, like the pruning remnants from flower farms. Consultancy Soil&More is – also in Ethiopia – talking to local rose producers about composting. Other obvious sources include manure from large poultry farms, household waste, sewage and slurry, the waste from biogas installations. Much of this is unused, but after processing it makes a good fertilizer.

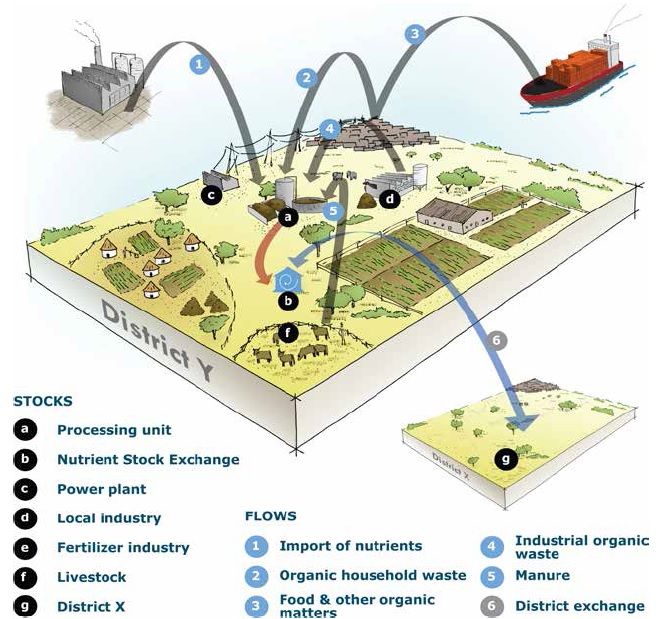

Make an inventory of the organic waste available and organise its distribution to African smallholders as a supplement to artificial fertilizer. This is a major component of the strategy proposed by the Fertile Grounds Initiative (FGI). Christy van Beek is coordinator of the initiative, which is supported by the Dutch ministries of Economic and Foreign Affairs, development organisation ZOA, Soil&More and the Alterra research institute. The proposed approach is based on an earlier, broadly based study into the best way of reversing the trend of ongoing soil degradation in Africa. Van Beek: ‘The conclusion was clear: soil fertility is less of a scientific issue than a question of coordinating and channelling nutrient flows to rural areas.’ Or to put it plainly: soil experts, don’t bury your heads in the sand but take a look around at what’s on offer.

Lack of training

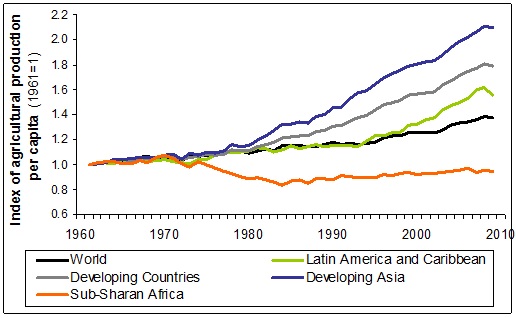

A major problem in Africa is that farming leaches nutrients from the soil which are hardly replaced. The continent lags far behind the rest of the world in its use of artificial fertilizers, deploying less than 10 kg per hectare compared with 98 kg in Asia and 120 in western countries. Nor are organic nutrients widely used. As a result, crop yields are falling – and that on a continent where the United Nations estimates the population is set to double over the coming decades. If things continue as they are, Africa will only be able to feed a quarter of its population in ten years’ time.

In recent decades agricultural production per head of population has risen throughout the world. Except in Africa. Source: FAOSTAT

Why do African farmers use so little fertilizer? For many smallholders artificial fertilizer is simply too costly. Purchasing on credit is usually not an option, because they lack access to financial institutions. And compost is not widely available. But ignorance also plays a role. Farmers often have no idea what specific inputs their land requires to generate better yields. Alternatives such as nitrogen fixation (by growing crops that help improve soil fertility, such as leguminous plants) or agro-forestry are still too rarely implemented. Effective education would make a major difference, but is often not available.

The most important resource of all

Early this year the Montpellier Panel – a group of eminent experts from Africa and other parts of the world – raised the alarm. Immediately prior to the start of the World Year of Soils, the panel said in a new report1 that almost two thirds of Africa’s arable land is too degraded for effective food production. Presenting the report, leading Indian soil expert Rattan Lal said ‘The best solution for problems such as political instability, environmental damage, hunger and poverty is the long-term revitalisation of that most important of all resources: soil.’ The Panel is arguing for large-scale investment by African governments and donors in land, soil and water management. What’s also important is that farmers be guaranteed the right to land, for farmers who don’t know whether they will still be able to work their fields in years to come are not inclined to invest in the quality of the soil.

That African farmers need to revitalise their land is undisputed. But there’s a fierce debate raging about how this can best be achieved. Many African governments and agricultural experts see the answer in a massive deployment of artificial fertilizer. But others – including the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) – are lobbying for a greener approach in the form of conservation agriculture, the use of organic waste and nitrogen fixation. However, the problem this often poses for farmers is that such techniques are far more labour intensive than applying artificial fertilizer.

A woman applies fertilizer on a maize crop in Kenya. Fertilizer is expensive in sub-Saharan Africa. Many smallholders farmers can only afford to apply a little fertilizer on their farms. Source: CIMMYT

Christy van Beek calls choosing between these two options ‘a simplification’. The FGI approach is based on integrated soil fertility management, which makes use of both mineral and organic fertilizer. What’s more, it takes as its starting point that an effective approach is location-specific, taking into account the needs of the particular soil. Now farmers often start fertilizing without having done any soil testing. To tackle this problem Alterra is developing a Soil Fertility Kit, a user-friendly digital programme that allows the farmer to input data about the fertilisation used, the acidity of the soil and the crops he wishes to grow. That’s presuming the farmer in question has a computer and electricity. ‘But,’ says researcher Tomek de Ponti, ‘it might also be the laptop of the local agricultural officer.’ The programme supplements the farmer’s input with the available data from research institutes, such as information about regional soil quality and climate change. The combination of the available information results in a fertilization recommendation. ‘On the technical side we’ve cracked it’, says De Ponti. ‘What we’re working on now is the financing so that we can make the tool widely available.’

What’s striking is the interest shown by Dutch companies that purchase agricultural products from Africa. De Ponti cannot yet name names, but Christy van Beek says that the attention signals a major change: ‘Companies are increasingly realising that they need to do something about soil fertility to secure their product supplies.’

Clever combinations

After having ascertained the fertilization requirements, the next step is to find out what is locally available. Van Beek: ‘In remote regions farmers will at most have their own compost heap. There won’t be anything else for miles around. But in areas with higher levels of economic activity you’ll also find more agricultural waste products. We want to inventory supply and demand and match them.’ In areas where insufficient compost is available, the solution will be to turn to artificial fertilizer. ‘It’s about clever combinations’, explains Van Beek. ‘With the right amount of artificial fertilizer you can give the soil an immediate boost. That can be tailored in a highly efficient way to the specific crop and to the seasons. Compost will help revitalise the soil for the longer term.’ Training sessions and demonstrations at a local level are essential to ensure the correct application. Such sessions must also emphasise green alternatives, such as growing leguminous plants and conservation agriculture.

The model envisaged by the Fertile Ground Initiative is shown below:

Dynamic platform

Over the coming months researchers will investigate whether the proposed approach can work in practice, starting in Ethiopia, Burundi and Uganda. The aim is not to start new projects but to implement the case studies within the framework of existing projects or programmes, numbering two or three per country. In addition task forces have been set up in the three countries, incorporating not only government and agricultural institutions but also private players such as laboratories, manufacturers of artificial fertilizer and composters. They will draw up plans to transport the required nutrients to where they are needed – which will often be remote and isolated rural areas.

Another important issue is the extent to which the plans are economically viable: high transportation costs could prove a major hurdle. But so far the ambitions are intact: ‘The ideal we’re aiming for is a dynamic platform where nutrient supply and demand comes together and where locally available nutrients are supplemented by external inputs.’

Footnotes

- 1. No Ordinary Matter: Conserving, restoring and enhancing Africa’s soil. Montpellier Panel, Dec. 2014.