Potato takes precedence over combating subsidence – Land users in no hurry to implement measures against subsidence

To contribute to the objectives of the IYS 2015, the F&BKP commissioned ImpactReporters to publish seven background articles on themes related to international soil and land use and enhancing food security. The fourth article ‘ Potato takes precedence over combating subsidence‘ has been written in Dutch by Stijn van Gils and was published on the Kennislink website on September 1, 2015. Please find below a translation of the article in English.

Potato takes precedence over combating subsidence

Many of the world’s deltas and coastal regions are slowly subsiding, often through water abstraction. Rehydrating the land can combat subsidence. But only if governments and farmers are prepared to act, by implementing measures such as flexible water level management or the cultivation of crops that can thrive in wetter soils.

Cycling through the Dutch polders one comes upon some strange anomalies. Like a marshy nature conservation area situated on high ground while dry, compacted fields and pastures stretch out below. This kind of subsidence can be seen in many places across the world. ‘In some deltas the level of subsidence exceeds the expected rise in sea levels’, says Marcel Silvius of Wetlands International. ‘Particularly in countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia it’s a major problem. There’s no money to build dykes and the soil becomes unusable for growing crops. As a result millions of people are faced with the threat of losing their land.’

Photo: South-East Asia has the worst subsidence. As a result millions of people face the threat of losing their land. Photo: Flooded fields in Malaysia

Reclamation

A major cause of subsidence is land reclamation, often undertaken for agricultural purposes. In sandy soils this doesn’t pose such a problem: grains of sand are big and coarse enough and the water from the soil is simply replaced by air. But the finer clay soils react differently: when the water is extracted the soil is compacted and the ground subsides. But compacting can also be caused by the use of heavy vehicles or farming equipment or through the laying of roads or pavements. In addition activity in the soil’s substrata, such as the extraction of ground water or gas production, can result in the ground subsiding.

Peatlands are particularly susceptible to subsidence. Not only that, but they are also sensitive to drying out. Peat, after all, consists of little more than dead vegetation. If it becomes oxidised because the water has disappeared, the peatland will slowly disintegrate and lead to subsidence.

This 2015 film from Wetlands International on subsidence in South East Asia shows how much fertile land could be wiped out by floods in Indonesia and Malaysia.

As if that wasn’t bad enough, the desiccation and disintegration of peatlands also releases gigantic quantities of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. ‘In 2007 Indonesia was the biggest emitter of carbon dioxide after the United States and China, mainly due to peatlands oxidization compounded by peat fires,’ says Gilles Erkens, a researcher into subsidence at the Deltares research institute and the University of Utrecht. ‘Here in the Netherlands, peatland oxidization accounts for around three percent of annual carbon dioxide emissions.’

Jakarta and Bangkok

Subsidence has major adverse effects, Erkens says. ‘Particularly delta regions with major cities such as Jakarta and Bangkok are battling with big problems. In Jakarta subsidence has accelerated to some 20 centimetres a year, bringing with it an increased risk of flooding.’ South-East Asia is worst-hit by subsidence, but susceptible regions are to be found all over the world. ‘In the Netherlands, the peatlands in the west and in Flevoland province are at risk. Subsidence in these areas amounts to around one centimetre a year.’

Soil subsidence not only increases the risk of flooding, but can also lead to house sinkage. This house has sunk due to soil subsidence. Photo: Deltares

Erkens’ work involves predicting subsidence and its effects on a world scale. And that’s a good deal more complex than simply identifying the cause. That’s because sand (not susceptible), clay (susceptible) and peat (highly susceptible) often occur together. Not only that, but clay quality also varies throughout the layers and some types of peat will disintegrate faster than others. Last but not least, how the soil was managed in the past is also a factor influencing the degree of subsidence in the future.

Satellite data

Quite often there are various factors in play, Erkens explains. ‘For example, groundwater abstraction coupled with weak soil under pressure. We use various models to map the different causes. Often we’ll start with one particular model and if that’s a reasonable fit we’ll superimpose the next one.’

That’s an effective way of working in the Netherlands, because researchers are intimately acquainted with the soil’s composition and how the soil is managed. But for other countries there may be little or no information. In such cases Erkens models the land using data from radar satellites which reveal features such as differences in altitude and vegetation. ‘On a large scale the outcomes are pretty reliable.’

Slowing groundwater depletion

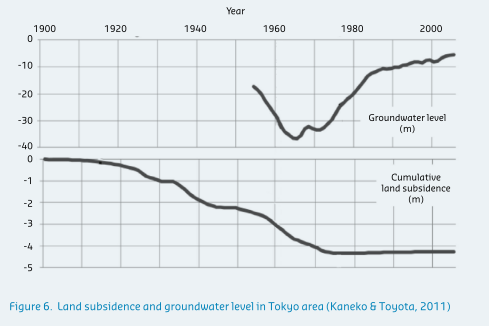

But solutions do exist. According to Erkens’ colleague at Deltares Marijn Kuijper, halting groundwater abstraction can slow subsidence or even bring it to a standstill. ‘Tokyo is a good example,’ she says. ‘Since the 1960s they have sharply cut back on using groundwater. As a result the water table has risen and subsidence has ceased. These kinds of solutions are put forward by Deltares in talks with the responsible authorities in other countries, such as Indonesia.’

In Tokyo, ground levels fell by four metres over the period 1900 to 1970. Since then subsidence has been halted thanks to a rise in the water table. The above table shows groundwater levels in metres below the surface (top) and cumulative land subsidence in metres (bottom).

Taken from ‘Sinking Cities’, a Deltares booklet; Original source: Shinji Kaneko & Tomoyo Toyota 2011. Long-Term Urbanization and Land Subsidence in Asian Megacities: An Indicators System Approach. In: Groundwater and Subsurface Environments: Human Impacts in Asian Coastal Cities.

Flexible water level management and controllable drainage

In areas where subsidence is caused by desiccation in the topsoil, flexible water level management is an option. In many farming regions people still work with a fixed summer and winter level, adjusting water levels just twice a year at a predetermined date. ‘Flexible water level management involves keeping water levels high for as long as possible, lowering them only when it starts raining’, Kuijper explains. ‘Often the land can easily stay wet for longer, for example during those times when the fields are not being worked or when little rain is expected.’

Controlled drainage allows for localized decision-making on where and when water should be drained off, Kuijper explains. Just like normal drainage systems, it involves pipes below ground to conduct the water. However, these pipes are often dug in deeper and closer together than in traditional drainage systems. Another difference with the traditional system is that the height of the exit pipe opening can be adjusted in order to determine whether water will be drained away or not. At times one might want to position the pipe opening a little higher, at other times a little lower.

Restoring peatlands

Gerard van Meurs believes that subsidence in peatland regions can also be reversed. ‘Peat is organic matter and can thus be replenished,’ he says. A researcher at Deltares, he helped develop TopSurf, a product to do just that. ‘This mixture of matured sludge, dung and organic waste has great potential for the polder’, Dutch popular science site Kennislink judged in 2011. ‘It can even result in raised ground levels,’ Van Meurs said at the time. Even so, nowhere in the Netherlands has TopSurf been fully implemented as yet. Van Meurs: ‘Land users and other parties also have competing interests.’ Replenishing organic material costs money and the effects of subsidence are seldom seen as urgent.

Photo: ‘This mixture of matured sludge, dung and organic waste has great potential for the polder,’Kennislink wrote in 2011. But there is also criticism of TopSurf. Photo: Visual Aspects