Think twice before ploughing

To contribute to the objectives of the International Year of Soils 2015 (IYS 2015), the F&BKP commissioned ImpactReporters to publish seven background articles on themes related to international soil and land use and enhancing food security. The first article ‘Think twice before ploughing’ has been written in Dutch by Marianne Heselmans of ImpactReporters and was published on the Kennislink website on April 28, 2015. Please find below a translation of the article in English.

Think twice before ploughing

Should you dig your garden or plough your fields or not? An increasing number of allotment holders and farmers have stopped tilling. It saves on hard work and soil life stays intact. But it makes things easier for fungi and weeds. ‘Only turn the soil if it’s really necessary,’ says the Belgian agro-ecologist Johan Six.

“I don’t plough at all anymore,” says Wridzer Bakker. The farmer and his son grow cauliflower, celeriac, potatoes, oats and wheat on their arable farm in the village of Munnekezijl in the northern Dutch province of Friesland. Up until ten years ago Bakker ploughed crop residues back into the soil each year, so achieving a clean and aerated seedbed. But ploughing also killed soil life. Starting in 2004 he began to experiment by leaving increasingly large areas of land untilled. “We see more earthworms, the crops root better and the soil is looser. And yields have increased.”

This promotional video shows how Wridzer Bakker cultivates his crops using no-till farming methods.

On the land

Bakker is one of a steadily growing group of farmers across the world that no longer plough all their crop residues under. Taken together, close on 10 percent of the world’s arable land is no longer tilled. Eighty percent of the farmers on the outstretched fields of gentech soya in Brazil no longer plough their land while in the Australian wheat sector it’s already 90 percent. Crop residues are simply left to lie on the land, after which the new crops are sown between them.

In Malawi the majority of smallholders do still plough their maize fields after harvest, often with the help of oxen. And most Dutch arable land is still deep ploughed with the aid of heavy machinery. But things are changing in Europe and Africa too, thanks in part to agricultural experts who have started to promote conservation agriculture. This more soil-friendly form of agriculture, supported by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) includes calling a halt to ploughing. In addition it involves more frequent changes of crop and leaving crop residues to lie on the land.

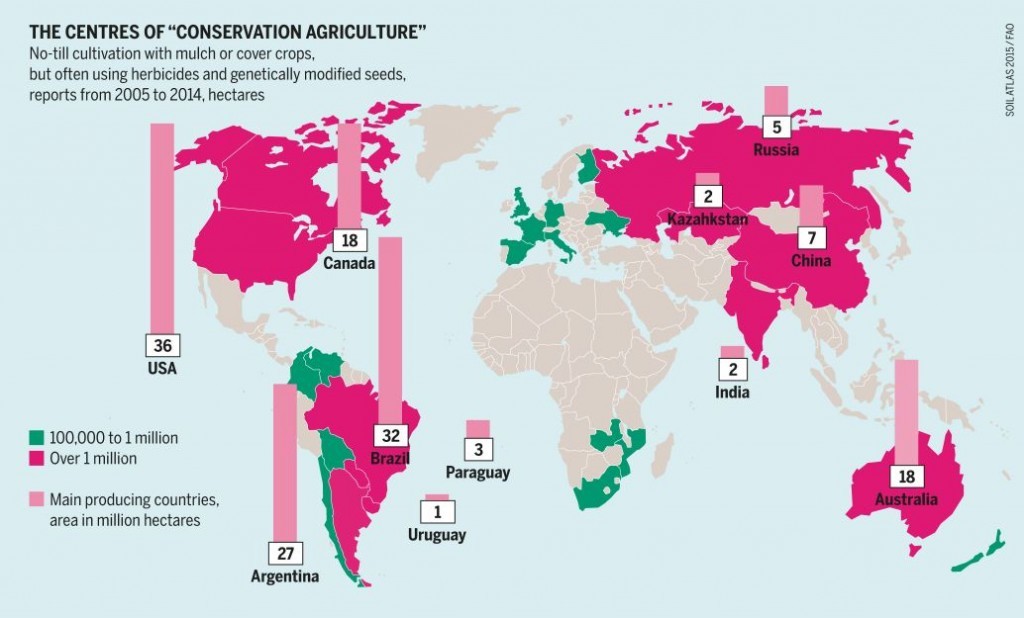

This map from the 2015 World Soil Atlas shows that no-tillage farming is most frequently practised in Brazil, Canada, the United States and Argentina. In these countries it’s mainly the large-scale soya and maize farmers who have stopped ploughing (although they often use pesticides and grow gentech crops). Countries shown in green: 100,000 to 1 million farmers; countries in magenta: more than 1 million farmers. The pink bars indicate how many million hectares fall under ‘conservation agriculture’.

Soil erosion

Proponents of no-till farming name various advantages of this method. Tilling to a depth of more than 20 centimetres – which is what farmers and most smallholders generally do – kills practically all soil life. This deprives the plant of nutrients, so requiring the addition of more fertilizer. Another reason is that in the previous century some US cities suffered from huge clouds of dust coming off neighbouring stretches of soy and corn (maize) fields which at that time were still being ploughed. And in South Africa, for example, arable land on slopes is often subject to erosion. After ploughing, when the fields are bare, they are more exposed to the wind and rain, and the soil is easily washed or blown away.

But leaving crop residues to decompose on the field also has its drawbacks. The residues become soggy, encouraging various fungal diseases. And because weeds are no longer ploughed under they can shoot up the following season. Well-off farmers are in a position to combat weeds with pesticides. In Africa, no-tillage farming can cost a great deal of extra effort, particularly for women. They are traditionally the ones who take care of the weeding, while the men are traditionally those who plough.

“You just shouldn’t take it to extremes,” says the Belgian agro-ecologist Johan Six, who visited the Netherlands last week to attend a conference on soil and agriculture. “It’s beneficial when farmers stop tilling the soil as intensively as they do now. But they mustn’t think that if they stop ploughing the earthworms will do their job for them. Sometimes you will need to plough deep.”

Five thousand field trials

Six, an agro-ecologist at the Federal Technical University in Zurich, has been studying the effects of tillage across the world for eighteen years now. The professor is a co-author of the biggest comparative study undertaken in the agricultural sciences to date, the results of which were published in the January 15 edition of the prestigious scientific journal Nature. In this study Chinese, American and Swiss researchers compared the yields of almost 5000 tilled and untilled fields with 48 different crops spread over 63 countries.

The study shows that no-till farming is particularly good for dry, non-irrigated fields — but only in those cases where farmers also take other steps to improve the soil. They need to shred crop residues and spread them evenly over the soil, fertilize well and frequently change crop. Farmers doing all of these things can achieve 7 percent higher yields than if they plough their land. That’s probably because the covered soil retains water better.

If farmers in dry areas simply stop tilling without taking any other measures, crop yields fall by an average 11 percent. Unfortunately this can happen, due to lack of money, time or expertise.

Fuel and time

In wet areas the results of no-till farming were the most disappointing. Average yields in Finnish wheat production and Polish maize production, for example, dropped by 10 percent even when the farmers took other measures to enhance soil quality. This was principally due to fungal diseases. And the no-till gentech soy fields in Latin America and the United States also sometimes underperformed their ploughed equivalents in terms of crop yield.

Even so, the authors of the article are certainly not claiming that ploughing every year is preferable. Six: “No-till farming does often help stop erosion, which impacts negatively on yields in the long term. In addition no-till farming on large tracts of land generates such a level of fuel savings that farmers are prepared to accept a drop of five to ten percent in yields.”

Averse to dogmatism

Six is averse to dogmatism and declines to issue blanket advice. Potatoes, maize, tomatoes, rice; warm, cold, clay, sand – every combination of crop, soil type and climate requires its own set of measures. “Farmers have to weigh up carefully what’s best, bearing in mind that it is good to till the soil as little as possible.”

Agricultural expert Wijnand Sukkel of Wageningen University and Research Centre agrees. “You can’t simply say that ploughing must be avoided. But nor should farmers deep plough every year as a matter of course.” His research group is now studying the effects or no tillage in the Netherlands. And some of the Dutch farmers are trying so called eco-ploughs (see picture), that till to a maximum depth of fifteen centimetres. Then the crop residues are ploughed back into the soil while preserving some of the soil life intact.

Japanese oats

Farmer Wridzer Bakker can see that completely inverting the soil is sometimes the answer. For example, when the ground is really too infested with weeds and fungi. But he feels he won’t need a plough for the time being. His farming operation grows a range of crops in turn, such as various types of clover, Japanese oats and celeriac. That way weeds and disease have less opportunity to thrive than in monocultures. Bakker has machines that have been adjusted to follow fixed paths so as not to disrupt soil life in the seed beds. And he uses solid manure rather than liquid fertilizer, which is better for the soil structure.

As such this Friesian farmer isn’t opposed to ploughing altogether. But he’s happy with his own decision to stop tilling. It has taught him a lot about the soil and about crops. “We’ve become better farmers.”

Shallow digging in the kitchen garden

Come spring and you see many allotment holders energetically digging up their vegetable gardens. Some even go as far as to rent a motor plough. But the Facebook pages and sites of allotment holders also list the disadvantages: digging disperses weed seeds, hurts your back, kills lots of beetles and spiders and turns the whole fertile top layer with rotted plant residues under. One of the most well-known proponents of no-dig gardening is the English gardening journalist Charles Dowding, author of seven books on natural gardening. In 1982 he stopped digging his vegetable garden on heavy clay in Somerset.

On his site you can see the result: abundant crops of lettuce, tomatoes, cucumbers, radishes, cabbages and many other vegetables and flowers. But the site also makes clear how much he has had to experiment with self-made varieties of compost and crop residues to keep weeds and disease in check. And it’s not every gardener who will have the patience for that.

“Effectively farmers and gardeners are faced with the same set of considerations,” says Wijnand Sukkel of Wageningen UR, who has an allotment of his own in Czechoslovakia. “Digging more than 15 centimetres down is often unnecessary. But particularly on unworked sandy soil weeds can really get the upper hand. And then it can be useful to completely invert the soil.”