Farmers are cherishing their trees again

To contribute to the objectives of the IYS 2015, the F&BKP commissioned ImpactReporters to publish seven background articles on themes related to international soil and land use and enhancing food security. The sixth article ‘Nigerien farmers are cherishing their trees again‘ has been written in Dutch by Marianne Heselmans of ImpactReporters and was published on the Kennislink website on December 8, 2015. Please find below a translation of the article in English.

Nigerien farmers are cherishing their trees again

Success stories from Niger, China and Ethiopia have proven that it takes less than 20 years to turn deforested and depleted soil back to green and fertile land, giving its people a future again. Ensuring farmers ownership of trees and land is crucial. Cooperation, knowledge and a long-term vision on its development are effective ingredients in greening an area.

Around 1980 Niger faced an enormous problem because the land in its over-populated southern regions, had become deforested and infertile. The revenues of the harvests of millet and sorghum had continuously decreased, leading to regular periods of famine. Funds to buy fertilizers were non-existent and the land had too few shrubs and trees and too little organic matter to keep the soil fertile. The unprotected fields were easy prey for the winds, and farmers had to sow at least three times per season as sand kept burying the emerging crops.

Twenty-five years later, in 2006, satellite images, analysed by the Free University Amsterdam and others, revealed decidedly greener fields. From the former 2 to 3 trees per hectare, they now showed 20, 60 and up to 100 trees. What had been the main key to success? The farmers in the southern region of Nigeria started to protect and cultivate the indigenous trees in an area of 5 million hectares, larger than the whole of the Netherlands.

Collect firewood

Chris Reij, professor in Sustainable Land Management at the Free University Amsterdam and senior scientist at the World Resource Institute, has been monitoring the region for years. ‘Now that there are trees in the fields again, women need only spend half an hour a day to collect firewood instead of the 2.5 hours they needed in 1985’, he says. ‘The trees protect the crops against the wind and help in revitalising the soil. Some trees also produce leaves and fruit that can be used as fodder or food.’

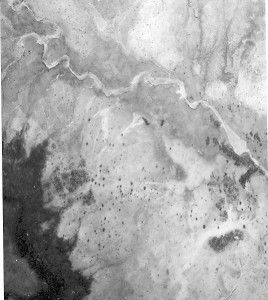

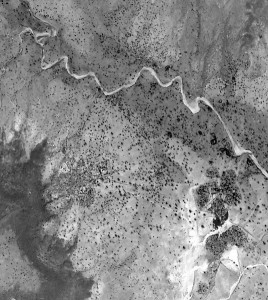

Satellite images showing the greening of the Southern Niger village of Galma. The dots indicate trees: to the left an image from 1985 , to the right from 2006. Photo: Gray Tappan, USGS

Currently, Niger is not the only example of large-scale greening. This autumn, Dutch entrepreneurs and scientists accompanied Dutch King Willem Alexander to the Löss Plateau in China. In 1995, the Chinese government started greening an area of 3.5 million hectares, financed by a 500 million euro loan from the World Bank. The slopes in the valley of the Yellow River were badly eroded by deforestation and broad acre cereal crops: the fertile löss continuously eroded away through wind and rain. Yields decreased and the hydropower plants in the valley clogged up. During their visit, King Willem Alexander and the entrepreneurs and scientists could see for themselves that many slopes were fertile and green, and that trees and perennials retain the moisture in the soil and offer shade, fruit, fodder and firewood.

The Löss Plateau in 1995 and as it is now, thanks to a well-coordinated programme of the Chinese government. Photo: John D. Liu

Protection of predation by goats

What do these successes teach us? Since 1995, Coen Ritsema, professor Soil Physics and Land Management at Wageningen UR, has been involved in the greening of the Löss Plateau through monitoring and scenario studies. ‘Well-targeted and quick measures can green a depleted area in 15 years’ he says. An example of such a measure for the Löss Plateau area was that farmers refrained from allowing their goats to roam free which quickly ended the predation of all vegetation on the slopes.

Furthermore, farmers with fields on very steep slopes were advised to grow fruit trees or perennial crops rather than wheat and sorghum, as perennials increase soil stability. Many farmers were paid to build terraces and small basins to retain the sediments and collect the water. ‘China’s government can react quickly and authoritatively, Ritsema states. ‘When we had shown them that erosion could be stopped, and what that could mean for agriculture, they immediately changed their policy. A similar process in the Netherlands could take many years, among other things because of public consultation procedures.’

In this film, (20 minutes), film maker and ecologist John D. Liu shows how the Chinese turned the Löss Plateau green again in just fifteen years, and how the Ehitopians turned their land in just a few years.

Willem Ferwerda, director of Commonland, an organisation for the development of large-scale land revitalisation projects, took part in the Dutch delegation visiting the Löss Plateau in October 2015. For each individual project, based on a business case, he tries to find investors. ‘A long-term vision for a large area is what works best’, says Ferwerda. ‘And it is important to ensure that farmers and other inhabitants of that area immediately benefit from the new policy. In the Löss Plateau, for instance, farmers were paid for their work on the development of terraces and planting, after which they were able to gain ownership of the land they had just developed.

Also, easily obtainable loans were available to change to a more soil-friendly sustainable type of farming, such as growing trees or keeping goats in fenced plots. Many farmers with fields on extremely steep slopes, changed to a job in industry or adapted their farming. Generally speaking, the greening policy was so successful that earnings in 2005 were much higher than in 1995. The investment paid off.

Protection and cultivation of indigenous trees

More and more Nigerien farmers started to protect indigenous trees, says Chris Reij. The UN International Fund for Agricultural Development played a prominent role in the promotion of this endeavour by setting up local organisations for the cultivation of indigenous trees. Reij states that during the famines in the Eighties farmers only had two choices: either leave their fields or change to intensification of agriculture with the help of indigenous trees. The latter development was assisted by the fact that before 1985 trees were considered to be government property, but after 1985 the farmers considered the trees on their lands to be their own responsibility.

A couple of successive and sufficiently wet seasons provided more good fortune for the endeavour. The trees had time to root well and deep enough to weather the following dry seasons. Ritsema: ‘Uncertainty about changing seasons should obviously be taken into account in the different scenario studies.’

A farmer in Burkina Faso cuts a ditch for planting perennial crops or indigenous trees. More and more regions in Africa follow the southern Nigerien example. Photo: Chris Reij

Indigenous undergrowth by means of Robinia

All experts agree that native trees and shrubs are preferable for greening a region. Sometimes, however, exotic species, if they are considered suitable to the area, are to be preferred. For instance in the Löss Plateau the Chinese planted the fast-growing, nitrogen-fixing tree Robinia. ‘Ecologically speaking not the best of choices’, says Ferwerda, ‘but appropriate from a social perspective, for these trees provide shade and improve the soil fertility.’ This autumn, the Dutch delegation noticed much native and natural undergrowth – thanks to the Robinia.

An integral view

During the visit, Wageningen UR signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the knowledge institutes on the Löss Plateau. Ritsema, whose scientific group has been working on the scenarios for land and water use for the last 20 years, says ‘a continuous integral view of the process in the region is important.’ For instance, planting Robinia trees on the steep slopes has had consequences for the rivers. Less and less sediment is deposited in the rivers, and the soil and plants in the region retain more water, resulting in a reduced water level in the rivers; at the same time the expanding cities downstream demand more and more water. How do you solve this dilemma? Ritsema: ‘Discussions on the possible choices need to be held with all parties concerned.’

Almond trees in southern Spain

Experts state that the stakeholders are farmers, local entrepreneurs, investors, governments and knowledge institutes. The initiators should form long-term relationships with all parties concerned. Willem Ferwerda’s organisation is doing exactly that in southern Spain. Farmers are determined to plant almond trees on degraded soils as this will enrich the soil and there seems to be a growing demand for almonds. Together with these farmers, the local organisation Alvelal, with the help of Commonland, analyses which composts are suitable for almond cultivation whilst also revitalising the soil. (See main picture: Farmers from cooperation Alvelal watching their almond trees in Southern Spain. Foto: Alvelal.)

Worldwide, Ferwerda discerns various greening initiatives that could be scaled up, such as the re-planting of the indigenous spekboom (portulacaria afra; elephant bush) in the Baviaanskloof in South Africa (currently 1000 hectares). The local farmers have agreed to create a 46,000 hectare goat-free area in exchange for the planting of herbs for the harvest of aromatic oils. However, Ferwerda concedes that things can go wrong, especially when the focus is on getting the maximum financial profit from a region; that inevitably leads to land degradation. In its recently published brochure and promotion video, Commonland explains the different kinds of profits from greening a region. ‘Nobody likes to live in a barren and degraded environment’, he says. ‘People want to work and live in a green and diverse environment. That is what gives meaning to their lives. That is what we need to make clear to investor.’

Ethiopian farmers sing at work

Ideally, local farmers and other entrepreneurs should initiate a regional process, as demonstrated by a 10 minute promotion film from 2014, made by the sustainable land and water management organisation TerAfrica. It presents images of farmers and experts studying maps together, and images of farmers singing at work. The film explicitly shows that the commitment of all stakeholders, land ownership for farmers, together with regional and zonal planning, worked well for the situation in the Ethiopian highlands. It concerns, similar to the Löss Plateau, a zone of high altitude and extremely steep slopes to be set aside for nature, a zone for extensive agriculture and a (valley) zone for intensive economic activities, including agriculture. The television documentary Groen Goud (Green Gold) introduced the situation at the Löss Plateau and in Ethiopia to the Netherlands.

Watch the Ethiopia film

Cultivating fruit trees is cheaper than reforestation

The World Resources Institute (WRI) estimates that 2 billion hectares of degraded soil can be greened. About 1.5 billion would be suitable for so-called mosaic landscape restoration in which a mix of forests and trees is used in combination with small-scale or ecological agriculture.

Up till now, the usual strategy for greening has been the planting of (non-native) trees by forestry organisations, such as the planting of the Great Green Wall in China as a wind break against dust storms. Since 1987, the Chinese have been planting fast-growing poplars and pine trees to the north of the Gobi Desert. By 2050, the project should result in a 4500 kilometres forested strip, according to the Economist. Such large-scale forestation, however, is expensive – 1000 to 6000 dollars per hectare – and moreover, monocultures are very disease sensitive.

Chris Reij estimates that the greening of 5 million hectares in Niger by farmers was realised with the relatively low cost of 100 million dollars. The cultivation and pruning of indigenous trees and shrubs has proven to be a simple and cheap method for further forestation and will lead to more productive types of agriculture. The costs are less than 20 dollars per hectare, according to the WRI.